The straight razor

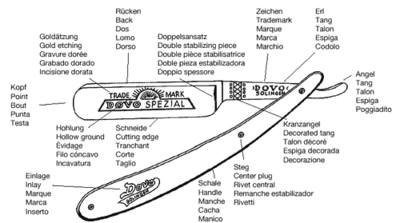

Basic straight razor anatomy[edit | edit source]

Orientation used in the description: the handle to the right, blade to the left, cutting edge pointing downwards.- Point/Kopf/Bout/Punta

- the left end of the blade.

- Blade, with a Back/Ruecken/Dos/Lomo

- the part of the blade opposite the cutting edge(Spine), and an Schneide/Cutting edge/Tranchant/Corte (pointing downwards).

- Tang/Erl/talon/Espiga

- the complete non-cutting metal part fixed to the blade, serving as a grip for the index, middle, ring, and little finger.

- Jimps

- ridges/notches along the tang present on some razors as a gripping aid. If present this is usually on the underside, but can occur on both top and bottom of the tang

- Double stabilizing piece/Doppelansatz/Double piece stabilisatrice/Doble pieza estabilizadora

- two close parallel vertical rims situated where the tang continues to the cutting part on the knife. Sometimes there is only one stabilizing piece. It is also referred to as 'shoulder'.

- Decorated tang/Kranzangel/Talon decore/Espiga decorada

- some sort of art where the blade stops and the tang begin.

- Handle/Schale/Manche/Cacha

- the part of the razor that contains the blade when closed. Sometimes it has an Einlage/Inlay/Marque/Marca (text, mark on the handle).

- Center plug/Steg/Rivet central/Remanche estabilizador

- the middle plug on the handle; Hohlung/Hollow ground/Evidage/Filo Concavo: the biconcave form of the blade in transection view.

- Gold etching/Goldätzung/Gravure doree/Grabado Dorado

- the mark or text on the blade.

- Trade mark/Zeichen/Marque/Marca

- the mark/text graved on the tang.

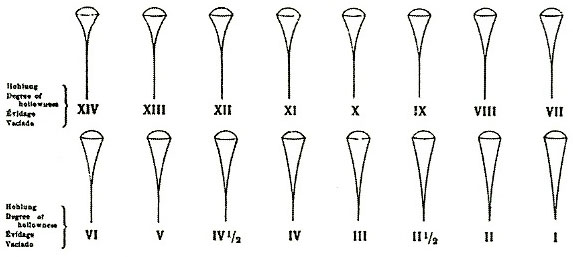

- The Ridge/Der Wall

- parallel to the back and the edge, running from point to the stabilizing piece, is a thickening of the blade, the purpose of which is to stabilize against torsion in the horizontal plane, and to give the edge elasticity. The stabilizing piece gives the blade torsion resistance in the vertical plane. If the ridge is close to the edge, it is called ¼ hollow ground, the lowest grade of hollow ground; if it is close to the back, it is called 1/1 or full hollow ground; ½ and ¾ are in-between.

The blade[edit | edit source]

Metal[edit | edit source]

Pure iron is a relatively malleable metal which cannot be honed to get a sharp edge. Steel is an alloy of iron with a certain proportion of carbon. Higher carbon content makes steel harder, thus allowing a sharp edge to be produced, but at the same time making it more prone to breaking. Steels used for straight razor blades (and cutlery in general) typically have 0.5-1.5% carbon by mass.However, the carbon content is not the only factor which determines the properties of a steel. Other metals are usually present, either intentionally added or because they exist in the iron ore : nickel, vanadium, chromium, molybdenum are among the main "steel modifiers". In particular, stainless steel by definition contains at least 10% chromium.[1] Many razors use stainless steel blades. The most obvious effect is that those blades are considerably more resistant to rus. Also, stainless steel razors generally can keep their edge longer, since the oxidation of the steel is slower.

Aside from the chemical composition, the properties of steel are also a function of how atoms are arranged inside it. This is a function of the forging process. When steel is heated to near the point of melting, and cooled down to ambient temperature slowly, the atomic structure evolves with the temperature. In fact the atomic structure rearranges at various temperatures below melting. However, by heating the steel slowly, and cooling it quickly (usually by plunging it into water), a blacksmith can force the atomic structure which normally exists at high temperature to be kept at low temperature (the atoms do not have enough time to move during the cooling). This process, known as quenching, was developed empirically by generations of smiths, and its infinite variations make much of the know-how in blade making.

Damascus is a sandwich of two different steels. Typically, one of them has a slightly lower carbon content, and the other slightly higher. The smith starts with two plates of each steal, and forges them together. After sufficient hammering, the bilayer can be folded in two, and the process is repeated until a thin alternance of the two steels is obtained.The carbon content is uniform in the final result. The obtained blanks is then forged, quenched and ground. Finally, it is exposed to an acid which oxidizes both steels differently, creating an interesting visual effect (see image below).

Widths and grinds[edit | edit source]

The width of the blade is traditionally measured in 8th (or 16th) of inch (a inch being equal to 25.4 mm). For instance, a razor with an 18 mm large blade is called a 5/8. Width varies from 3/8 to 8/8 (9.5 to 25.4 mm) or even 9/8, with 5/8 and 6/8 blades being the most common.

This is a chart by Henckels Zwilllingswerk:

This is the chart SRP uses for its razor database:

The smith can subtract a varying amount of steel to produce a hollow blade. The chart show various levels of hollow blades, from "extra hollow" to "true wedge". A hollow blade produces a crystalline sound while cutting a hair.

The main objective of hollow ground blades is to make honing much easier. On a true wedge blade, the honer has to remove steel on the whole flank. By contrast, on a hollow ground, only the very edge of the blade and the flank of the spine are to be thinned, which requires much less effort. The spine must rest on the stone (or the leather). It ensures that a constant honing angle is applied. During the lifetime of the razor, the blade is somewhat narrowed by successive honing cycles, but the spine is also thinned, thus the honing angle remains the same.

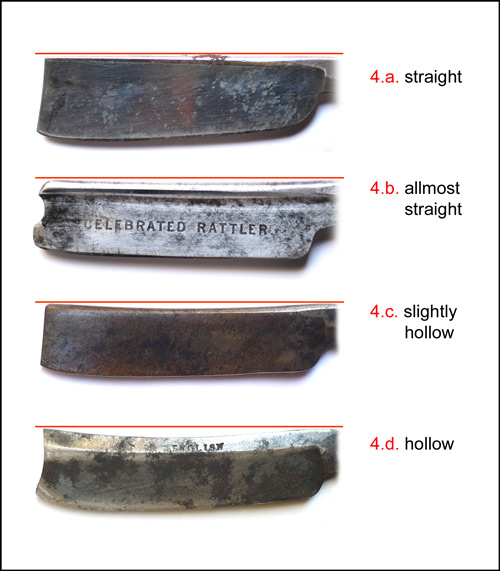

Single and double grinds[edit | edit source]

One of the simplest ways to remove metal from the sides of the blade is by contact to a grinding wheel, which carves out a circular segment resulting in a profile similar to this

However, more hollowing is easier to achieve with double grinding, carving out two overlapping circular segments. The resulting profile is characterized by a belly in between these segments similar to this

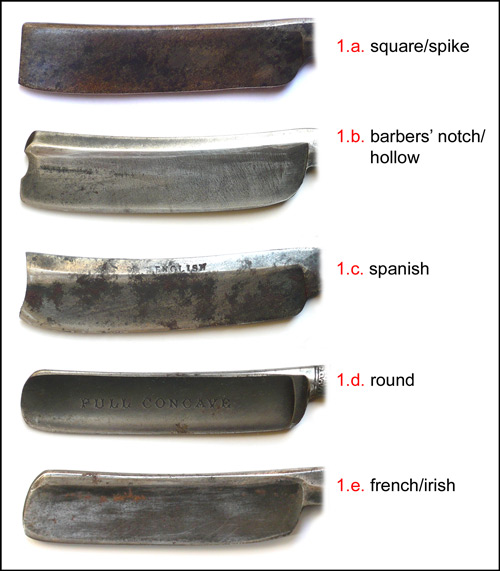

Point styles[edit | edit source]

The point of the blade can be shaped in several styles, the commonest being the round point and the square point (or ‘spike’). But there are also half-round, oblique, notched and French points. The sharp corner on the square point razor is useful for exact work, say, around the edge of a moustache. Whether sharp or round point is more dangerous the answer is that they both are in a different way. A sharp point does not provide any cushion against poor depth perception, while with a round point it is not clear where the actual cutting edge ends. At the end of the day it is a matter of personal preference, but as far as safety goes knowing exactly where the edge is at any moment is crucial.

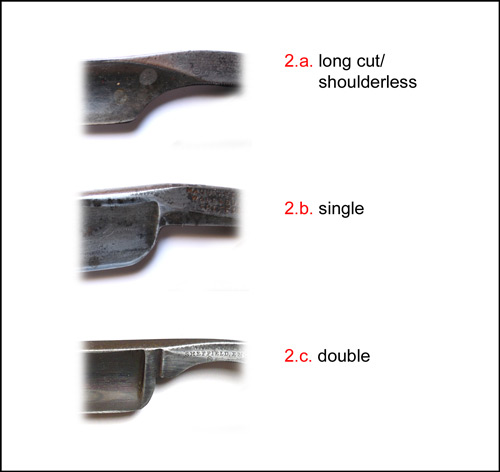

Shoulder styles[edit | edit source]

Shoulders are somewhat thicker parts at the "beginning" of the blade (near the tang), whose purpose is to increase the rigidity of the ground part. An extra hollow blade is, except at the spine, a very thin membrane of steel, which would lack stiffness otherwise.

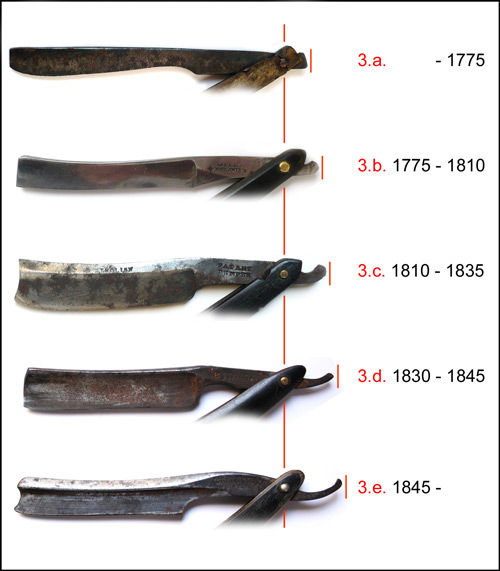

Tail styles[edit | edit source]

Spine styles[edit | edit source]

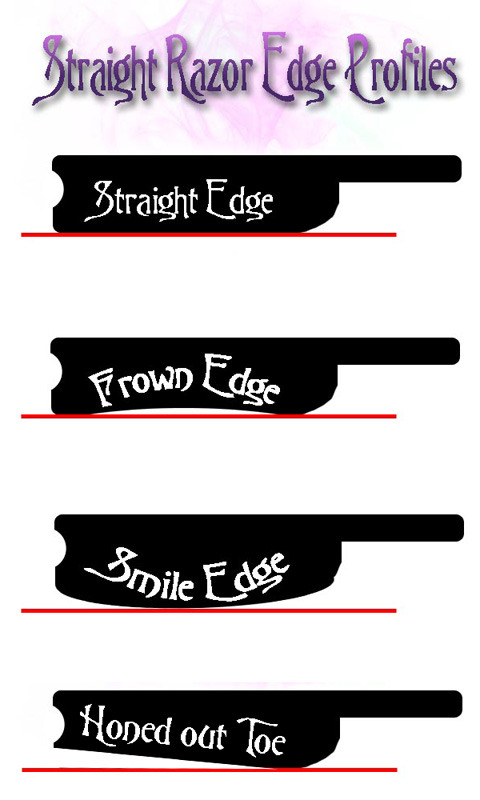

Edge Profiles[edit | edit source]

Scale materials[edit | edit source]

Scales come in a variety of materials depending on the price range, manufacturer, and era of the razor. Natural materials include wood and animal products, while plastics are also widely used. One must not be ideological about materials, as there are very good razors with plastic scales. Plastics scales are the cheapest to make from an industrial perspective, but require too much tooling for amateurs. Wood is therefore the preferred choice for homemade replacement scales, as it can be machined using artisanal tools.

Wood[edit | edit source]

Various kinds of wood, more or less "noble", are used to make scales. Ebony is hard, dense and lasting, it is used notably by the common Dovo Silver Steel "Ebenholz" (German for ebony). Boxwood is another good wood, used among other by Thiers Issard. Snakewood, Cedar, Bocote Rosewood, and Olive wood are among the quality woods used for scales.

Various techniques are used to protect the wood from moisture and mold : wax, varnish, epoxy coating... Using those techniques, wood becomes a long lasting material.

Metal[edit | edit source]

Stainless steels are a bit heavier than wood or plastics, but are lasting and noble. Dovo "All Stainless Steel" and Wapienica are among the widespread razors using this material. Aluminum scales can be found on vintage razors too. Silver is even used on some high-end antiques.

Animal products[edit | edit source]

Earlier razors used numerous materials derived from the animal reign. The use of those materials have declined, because of competition from cheap plastics and the ban of some materials who were derived from endangered species.

- Bone (typically from cattle) is still used on contemporary produced razors, ie Dovo "Bismarck" 5/8.

- Horn (from cattle, bison, buffalo) makes very good scales. This noble material requires specific maintenance (see Illustrated guide to fixing warped horn scales). Note that the same product (basically keratin) can be produced from cattle hoof.

- Mother-of-pearl (aka Nacre) is a very beautiful, but very expensive material, used by some high-end razors. The rarity (hence, the price) of large pieces of nacre means those scales are usually made of two or three assembled slabs (as in the exemple below).

- Turtle scales used to be a premium choice. Sea turtle hunting is now banned, preventing any legal supply of this product.

- Ivory[2], which makes the scales of some high-end vintage razors, is now banned, except in fossil form from mammoths (see Dovo "Mammut" 110).

- Pressed leather has also been used.

Dovo "Mammut" 110 with fossil ivory scales

Composites with natural fibers[edit | edit source]

Those materials are sorts of laminated, plywoods, and so on.

- Micarta was widely used at a time. It is a plastic (epoxy or cyanoacrylate) with embedded natural materials, such as linen, or even paper. See also : Making Micarta scale material

- Stamina is a similar material, made of wood and phenol.

Plastics and elastomers[edit | edit source]

Plastics are artificial polymers. They are generally classified between thermoplastics and thermosetting plastics. Thermoplastics, such as epoxy, turns liquid when heated enough, and are melt to mold a desired object. Thermosetting plastics, such as polyethylene, PVC, polypropylene, or Bakelite, are made from two or more reactants, which are heated to provoke the polymerization. Thus, it's the heating that created the plastic, and this process is not reversible. One created, the object can not be melted back, reshaped, nor recycled.

- Celluloid was historically the first thermoplastic ever, developed as a substitute for ivory (and still sold as faux ivory now). Made from a chemical reaction between cellulose (cotton, paper...) and nitric acid, made decay-proof by the addition of formol, it could be called a bioplastic. It's extremely flammable. Relatively few new straight razors use celluloid scales, except as faux ivory or faux nacre. However, regarding vintage razors, celluloid scales are usual, and sometimes decorated with elaborated reliefs.

- Various usual plastics are now used in the make-up of the scales of most entry-level razors made in the last few decades.

- Bakelite(commercial name for polyoxybenzylmethylenglycolanhydride) was popular in the first half of the 20th century. Like celluloid, it's one of the first plastics ever. This thermosetting polymer is produced from phenol and formaldehyde (both are basic products from the petrochemical industry), wood flour can be added as a filler.

- Rubber (natural or artificial) has also been used.

Buying razors[edit | edit source]

Serious issues[edit | edit source]

Frowning blades[edit | edit source]

When a blade is wider at the heel and the toe, it is said to be "frowning." A frowning blade is very difficult to hone if it can be honed at all and so should be avoided if possible.

Edge damage[edit | edit source]

Chips, nicks, or cracks in the edge can also prevent a blade from being honed. Very small chips or nicks can take many hours to hone out. Larger chips and nicks as well as cracks can mean that a razor needs to be reground before it is usable.Heavy pitting[edit | edit source]

Heavy pitting that covers a large portion of the blade will require sanding a lot of material off of the blade in order to get rid of the pitting and corrosion. If the pitting or the corrosion extend to the edge of the blade, it is likely that the blade cannot be made usable again and therefore should be avoided.

Micropitting

[edit | edit source]

Micropitting, or Devil's Spit, is very fine corrosion that can tunnel into the steel and cause damage beyond what you can see. Viewed with a good 10x hand lens it looks like random, black lines and pores. If it occurs along the edge, the blade may not be recoverable for shaving.

Extreme warping[edit | edit source]

A blade that twists or is otherwise warped visibly is likely to be difficult or impossible to hone. Many older blades maybe uneven when placed on a flat hone and can be honed by using specific techniques like a rolling hone stroke or a concentrated x-pattern. Extreme warping is observable with the naked eye and should be avoided.

Warped scales, however, can be fixed, cf. the Illustrated Guide to Fixing Warped Scales. It should be noted, though, that removing the scales may like result in breakage. A relatively safe way to remove and later re-attach scales is described in the Illustrated Guide to Un-pinning and Re-pinning.

Questions to ask a seller[edit | edit source]

Despite their best efforts, many sellers have limited knowledge of what is essential information to be put into a classified. If any of the following are missing from the description of a razor that is for sale, you may want to enquire further to avoid later disputes over lack of quality.

- When was the blade last honed?

- Is there evidence of micropitting?

- Does it center in the scales without the edge making contact on either side?

- Is the pivot pin tight?

- Are the scales original?

- Are there any cracks in the scales?

- Are there any hairline cracks in the blade?

- Do you have pictures of the (other side of the blade, close up of a certain area, etc)?

- Do you offer a return policy if I am not satisfied?

- If yes, what are the terms?